Dr. Susan Letzler Cole is a Professor of English and the Director of the Concentration in Creative Writing at Albertus Magnus College. Her previous works include Directors in Rehearsal: A Hidden World; Playwrights in Rehearsal: The Seduction of Company;The Absent One: Mourning Ritual, Tragedy, and the Performance of Ambivalence; Missing Alice: In Search of a Mother’s Voice; and Serious Daring: The Fiction and Photography of Eudora Welty and Rosamond Purcell. In Dr. Cole's upcoming book, They Made A List: A Memoir Beyond Memory, published by SDSU Press, she weaves together snapshots of her childhood, linguistics, child development, and etymology in a love letter to her parents.

This interview was conducted in April of 2022 by Toki Lee, editorial intern and marketing associate of SDSU Press.

* * *

SDSU Press: Please introduce yourself and your upcoming book in as many or as few words as you would like.

Dr. Cole: I'm Dr. Susan Letzler Cole, Professor of English and Director of the Concentration in Creative Writing at Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, Connecticut. My book, They Made A List: A Memoir Beyond Memory, is a personal story, but at the same time it's an exploration of our earliest acquisition of language, which is a process that is both magical and mysterious. How did we get to language? How does our earliest use of words define and shape who we have been and who we eventually become?

It has been said that the two greatest mysteries in all of nature are the mind and the universe. “You may have to travel 24 million miles to the first star outside our solar system to find an object as complex as what is sitting on your shoulders — your brain." So, in a sense, my book is a mystery story and it’s a story about a process we're all engaged in. It's a personal quest for linguistic origins: a journey that becomes everybody's. Despite recent and continuing research, exactly how the use of language arises in our infant life remains mysterious.

Some years ago I accidentally discovered my parents' list of the first 200 words I spoke at the age of 18 months. As I look at that and explore it, I'm looking at the gift of parents noticing how their baby learns and how we achieve selfhood through the use of language.

SDSU Press: That's very beautiful. Now, this is a very personal topic to you. This is not your first book, however, that details your personal life. I believe you've written a book called Missing Alice that touches on adolescence, and your parents as well. What was it like writing about yourself and your life before you remember it? Is it hard to write about such an inherently vulnerable subject?

Dr. Cole: Well, it is hard. I'm writing about an initially speechless infant. At some point, I’m also trying to write about the fetus, what it would be like to be in the womb. I think that is a wonderful question — it didn't occur to me that it was hard. I've written a number of books and every book I write comes out of passion. Because this was a passionate subject for me once I found the list of my first 200 words, it didn't occur to me that this project might make me feel vulnerable or nervous, I just felt so… curious.

You mentioned my earlier experimental memoir, Missing Alice [the name of my mother]: In Search of a Mother's Voice. After my father died, for eight years I called my mother at the same hour every night, and then after she died, her voice was missing. I didn't think I could bear it and I began to write letters to her on my computer; then my computer failed. I took it to a computer shop, the man there opened the file and there were my letters being looked at by someone else, out there in the public domain, and so that became: Missing Alice: In Search of a Mother's Voice.

What happened with this new book was that again, I thought I was going to write about my mother. I thought, "Of course my mother would have made this list of 200 words!" Then, a dear friend looked at the handwritten list, which is printed in the book, and she saw two hands. And so, in some sense, this book is partly honoring my father. My father is always there in this book and in this list where my parents’ comments are intermingled. They Made a List is a record of parental acts of noticing and the importance of that: the importance of our parents noticing how we come to language.

|

| Dr. Cole and her mother, Alice |

SDSU Press: After reading about language acquisition and whatnot, do you recommend this to be a process for other parents? Do you recommend that other parents create a list of 200 words? What are your thoughts on that?

Dr. Cole: That's a wonderful question. First of all, I want to say, and I guess this isn't very modest of me… but 200 words at the age of 18 months, this is rather extraordinary. Yes, I would recommend that parents do keep lists.

This book actually began with a futile search for my first word. My mother was very organized. She put all the words that began with a particular letter beneath that letter in vertical columns and she did the whole alphabet. So I have no idea what my first word really was! Lots of people say, “I know what my first word was" because that's what their parents tell them, but in fact their first word could have been addressed to a teddy bear, or to themselves, or to a rocking chair.

To really know about your own early language, I think your parents have to record it. So I would recommend that any parent who has the time — both of my parents had full-time jobs, but somehow they were able to make this list — try to record their baby's earliest language, as it will mean as much to their children as what my parents did meant to me.

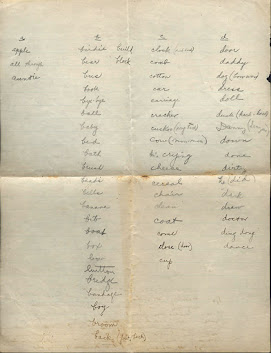

|

| The first page of the list, featuring letters A-D |

SDSU Press: Right right, so this list of 200 words — obviously very extraordinary for an 18 month old. Now that you sort of have a couple years into your life, do you see any words in that list that represent you as a person, or you look at that and say, "Oh, of course, I said that!" Anything like that?

Dr. Cole: Well, just to be silly, three-syllable words are very hard for a baby, and I only have one which is banana.

SDSU Press: (laughs) Did you like bananas? Do you still like bananas?

Dr. Cole: I don't think I did! But now, as an adult, I have a banana every morning. (laughs)

One word that isn't there is love. I saw love, I felt it, but the word love is not there in the list, and that's what's extraordinary to me, that that word is not there.

SDSU Press: You felt it as a kid you felt your parents’ love, but you never actually verbalized it.

Dr. Cole: Apparently, I was not able to say that word. We have to wait till our vocal equipment is ready to make certain sounds, and that may have been a difficult sound for me to make. Also, linguists have pointed out that sometimes babies just have preferences. Maybe the word wasn't as interesting to me as "tummy," which apparently I loved to say (smiles).

SDSU Press: It is a very interesting list of words. I can't remember all of them, but I think the most fun I would have as a kid is just saying the word apple, which is one of the first words on that list.

Dr. Cole: Oh, I'm so glad you said that! Yes, I love apples. I used to watch my grandfather, when he would come from New York to our northern Virginia house, cut his apples with a knife. He would cut the skin of the apple all in one long strip and it fascinated me, and the taste fascinated me, and applesauce fascinated me. I'm so glad you love the word apple.

SDSU Press: The sound it makes — apple — it's a very "front of the mouth" kind of word.

Dr. Cole: Oh, that's wonderful! I wonder if it could have been my first word.

SDSU Press: It's possible! On the similar but opposite side of that, are there any words that surprised you that were on the list?

Dr. Cole: I'm not sure that any actually surprised me but… well, yes, there was the word "otto.” Not any person that I can remember. I'm not quite sure why I was saying otto! Don't have a relative named Otto, no friend named Otto, I don't even think there was a children's book with the word "otto" in it.

SDSU Press: Interesting!

Dr. Cole: Yes, so that surprised me. What shouldn't have surprised me was the word Susan — I didn't realize that at 18 months, I could say my own name. My brother said "Su Sa" for a while, but I guess I could pronounce Susan, so that surprised me a bit. It was a surprise that I could say toothbrush! (smiling)

SDSU Press: That's a pretty good word for an 18 month old to say!

Dr. Cole: Uh huh! (laughs)

SDSU Press: Now, this is obviously a book very focused on linguistics besides the memoir and language as a whole. What was the research process for this book like? Was it any more challenging or less challenging than your other books?

Dr. Cole: Every book I've written has required research into what I didn't know. But this book required more, so I'm looking at linguistics, quantum physics, ethology, primatology, psychology, anthropology… On the one hand, They Made a List required more research than any other book I've written. But at the same time, all of that research was simply fascinating. Not just that I was learning new fields, but the kinds of research I was able to explore. Let me give you an example of something that I hadn’t known about birds. Science increasingly views human speech and birdsong as products of convergent evolution, given that songbirds and humans share at least 50 genes specifically related to vocal learning. That is fascinating and it's the kind of thing that my research, in this case, produced. I'm not sure if I'm answering your question, but the research in itself became so interesting that I loved doing a lot of it.

SDSU Press: It was sort of like reading and writing. It became its own beast, basically.

Dr. Cole: That's nice, what you just said. Yes, reading and writing were interwoven.

SDSU Press: That's beautiful. Speaking of writing, this book — as far as I've seen from the manuscript — was written in a sort of anthology format. You had the title, and then you had the paragraph, and after you flip to the next page, it'd be a new memoir. A new memory, so to speak. Is there a reason you chose to write in this format? Is that what you're just comfortable with? Tell me about that.

Dr. Cole: The book is really a series of mini-chapters, and that's the way it happened. I would have a moment of meditation, or a sort of burst of light, and then it would be over, and it would be written. And then later, there would be another burst, and I would write it, and it would be over. Because that's the way the bursts of light came to me, that's the way the meditations came to me, that's the way I presented them in the book. The book is a series of reflections on a process that I think is universal, which has to do with trying to understand how language first comes to us as humans– and how language may come to non-human animals as well. The different mini-chapters are different lenses for looking at the same subject.

SDSU Press: Like a kaleidoscope.

Dr. Cole: Yes! Exactly. So they had to be separate.

SDSU Press: I think it's a wonderful way. I think it really is reminiscent of what looking back in your childhood feels like: these little moments you remember very vividly, but you have no context for, almost.

Dr. Cole: I would like to have what you just said be a part of what we're doing. I love that! I hadn't thought about that, but it is like what happens to us in childhood. That's great.

SDSU Press: Is there anything else you want to say or touch upon? Any closing remarks?

Dr. Cole: I think those are wonderful, wonderful questions. I would like to add that the job of a baby is to learn. To learn about a new world, a new place outside the womb. In They Made a List: A Memoir Beyond Memory, of course I cannot remember what it was like to be 18 months old.

I do think that the book would appeal to anyone interested in the relation of parents and children, the problematic nature of human communication, the development of voice and selfhood. And I think it would be of interest to anyone who has helped or watched a child find a way to language or, as a child, been helped toward language – that is, to any of us.